Visualizing writing

Tips from Kelley Edits

Hello, fellow writers!

Do you ever feel as though you’re reinventing the wheel when it comes to your research and writing process?

It’s true that everyone’s approach will be unique. But it helps to know about other people’s habits as you refine yours. This post was inspired by conversations with my friend, the wonderful art historian Mirela Tanta, a longtime collaborator with whom I share a love for the visual.

Over the summer, Mirela emailed me from Romania, where she was doing Fulbright-sponsored research and teaching. She wanted to know if I had ever used Scrivener because she was looking for new ways to organize her notes and ideas.

I hadn’t, but the question stimulated some great chat and also a smack-my-head, “of course!” realization that might help you if you’re reevaluating your process.

Mirela’s methods

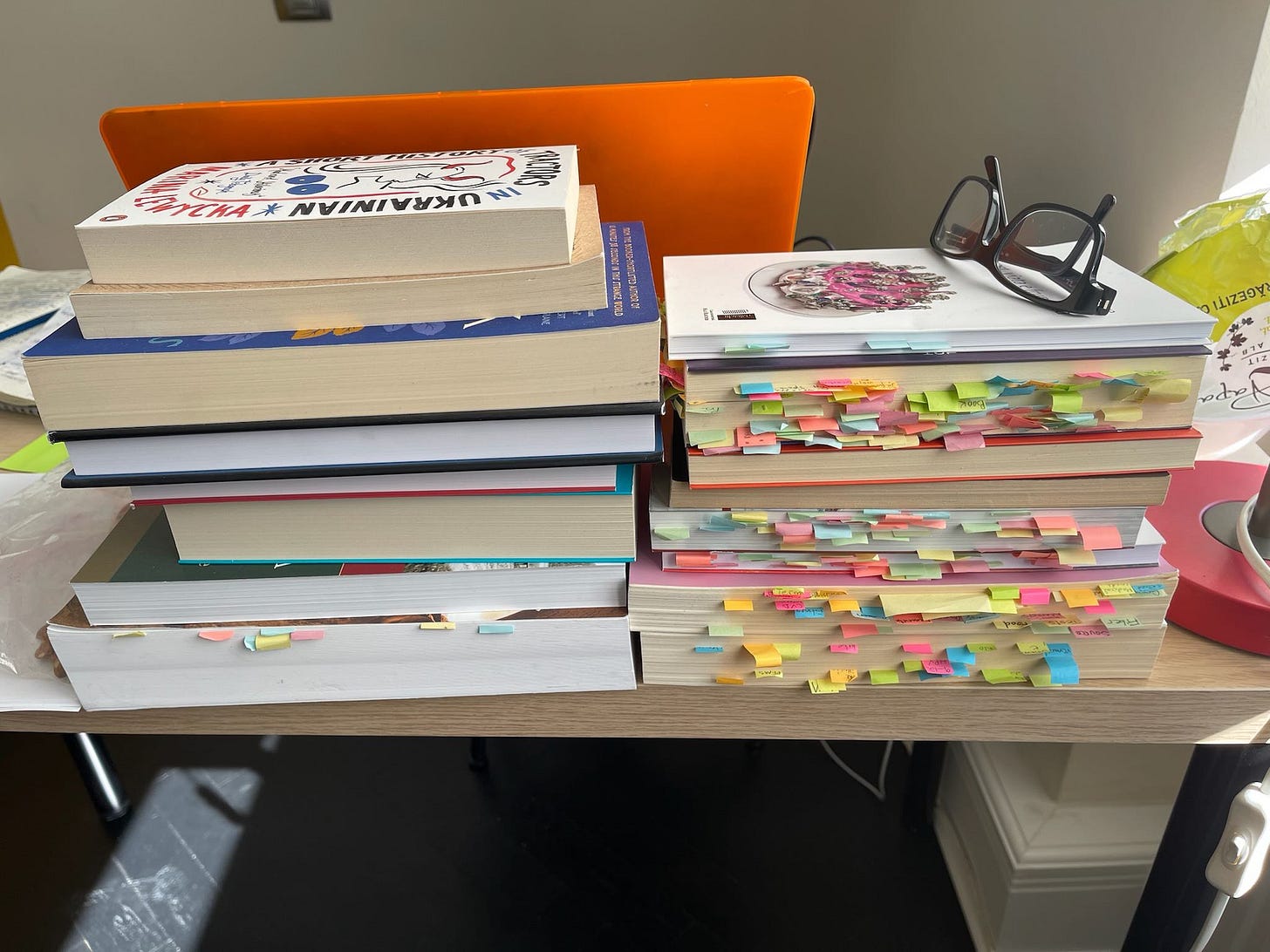

As part of her initial email, Mirela sent me a photo of her books, studded with color-coded sticky notes for tagging important ideas that she discovers while reading. It was this process she wanted to jettison, writing, “This is how I work. You can see my dilemma.”

But as it happened, Mirela’s process is far more detailed than this one photo suggests.

She also keeps two notebooks. One corresponds to the research and the sticky notes, recording important finds. The other is for brainstorming. (They’re old-fashioned analogue notebooks—her husband recently gifted her a smart notebook, but she tells me that so far it’s been staring at her from a corner of her desk.)

Also, now that she’s returned from a fruitful year of research, primed to start working on her book project, she’s picked up another old research habit.

In the past, she visualized a large-scale project with a long paper scroll that she stretched down a hallway at home, noting every idea “so that my head didn’t explode.”

Now, she has started a similar project, pinning anything meaningful to her—objects and ideas that inspire her—to the walls of her office.

Comparing notes

Though Mirela thinks of her process as disorganized, I think it’s probably unavoidable, even necessary, to feel as though you’re swimming in a sea of chaos at the beginning of a project.

I know I did, even though my book was based on my dissertation.

Like Mirela, I also needed a hands-on approach to getting my ideas together. But rather than paper, I settled on a whiteboard to record my changing thoughts. Periodically, I needed to move on and create a new, updated record of my progress. So, I’d take a picture and then erase the whiteboard and start fresh.

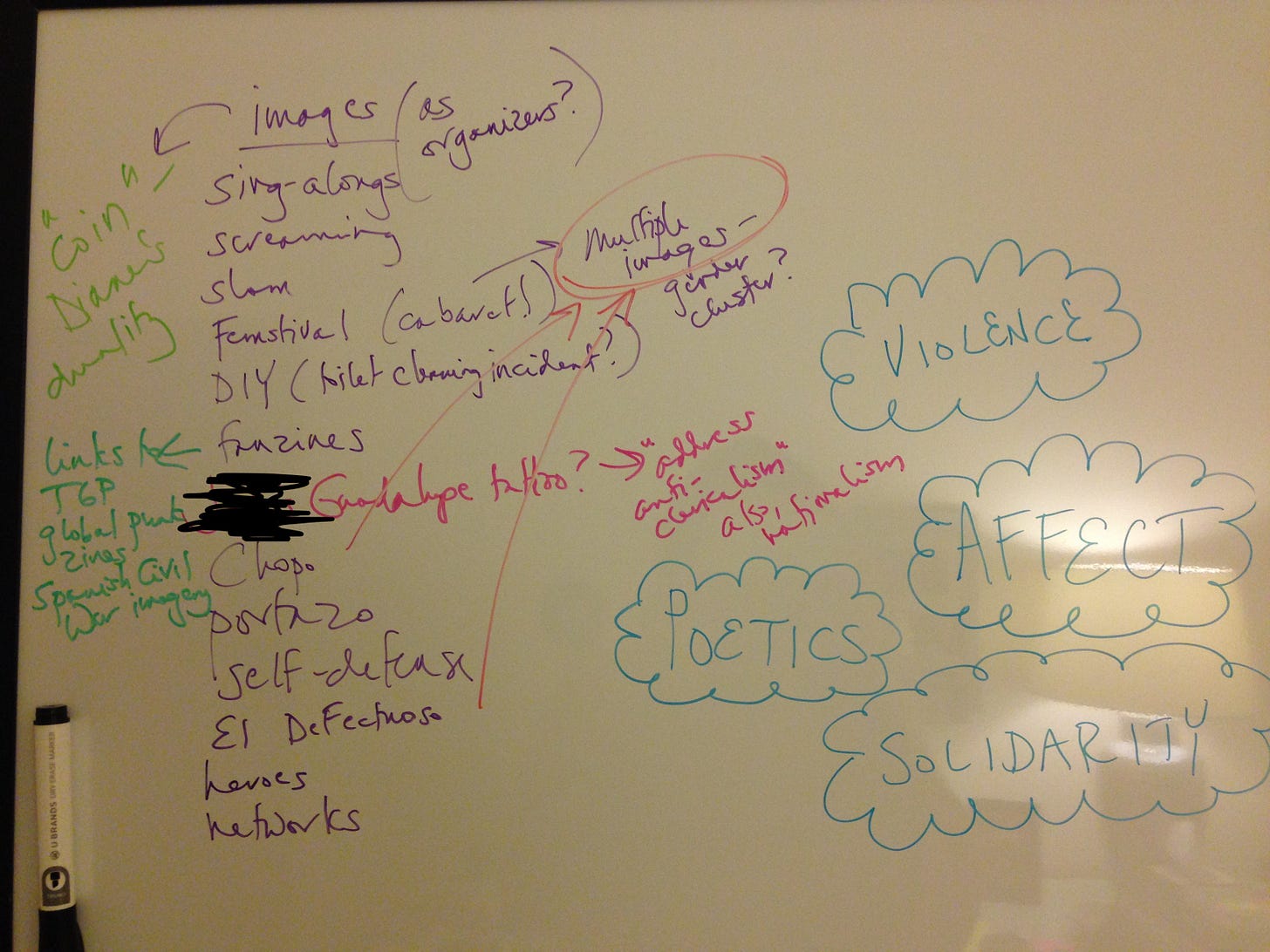

Here is a look at an early stage of visualizing my writing:

You can see that my ideas were quite rudimentary. I’d drawn cloud-shaped bubbles around potential major themes while putting a list of anecdotes that could open up discussion on those themes vertically.

It helped to just start assembling ideas to see how they could be rearranged. Writing stuff down encouraged me to feel like I was making progress. It was tangible evidence that I had plenty of material, and some of it began to make more sense as I reworded concepts or put them in a different place, nearer to another cluster of ideas.

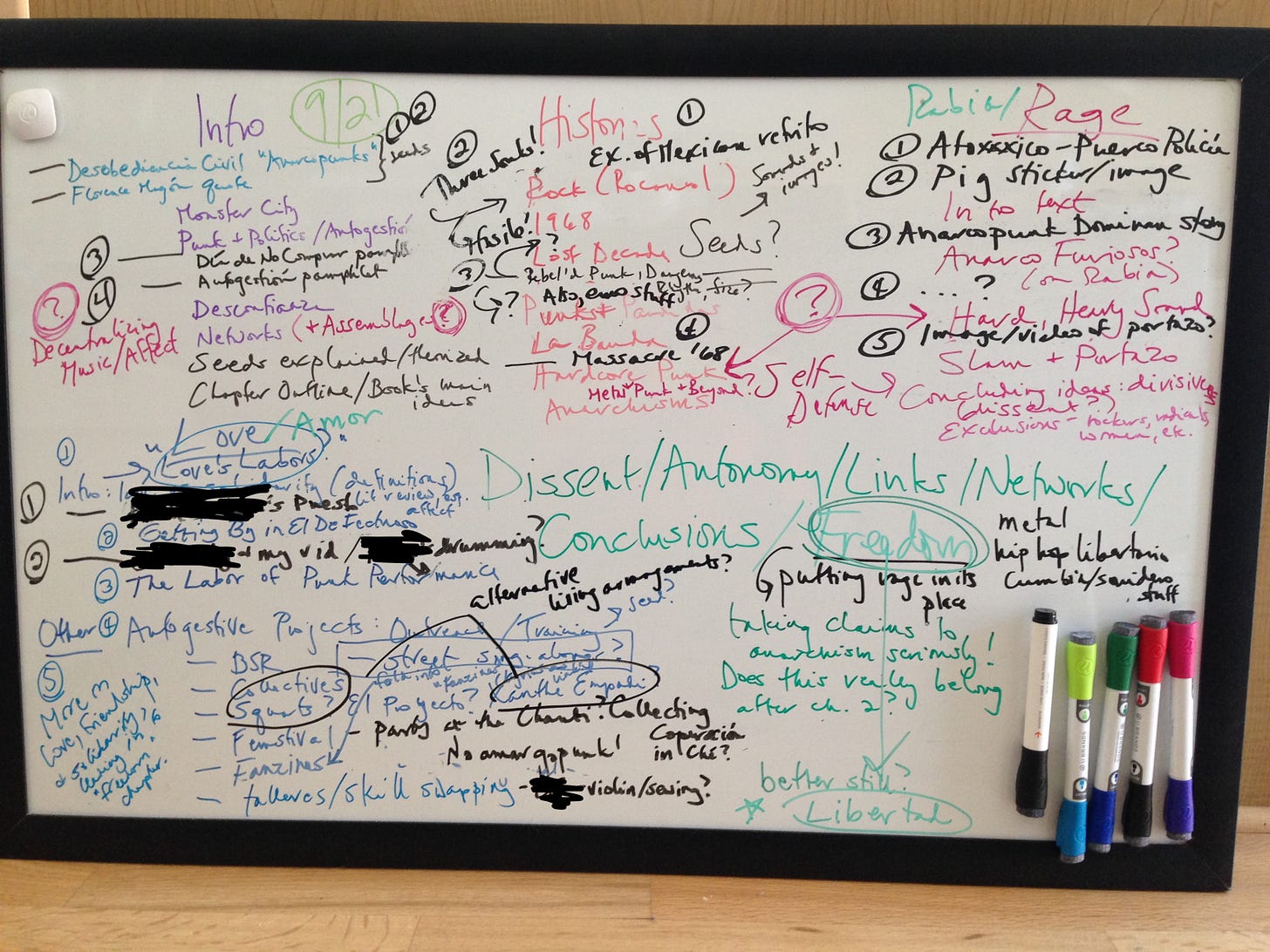

Here is another photo, taken over a year later:

By then, I’d fleshed out the major themes into chapter areas and noted the different sections and pieces of evidence I’d include within them.

I was beginning to feel like I had a coherent structure in place—though if you look at my finished table of contents, you’ll find that I still had some big reorganizing ahead.

Surely it’s not a coincidence that the chapters were starting to look more linear, like conventional outlines, with different colors, shapes, and arrows providing still-percolating thoughts about how to connect the seemingly static bits to remaining questions and ideas.

Through my hands on the whiteboard, the chaos in my head gradually resolved itself into something orderly, with the major themes and arguments connecting one chapter to the next like the narrative arc of fiction.

Storyboarding for nonfiction writing

Spurred by my chat with Mirela, I went looking for evidence that other academic and nonfiction writers work as we do. And lo and behold, our methods have a name!

All along, we’d both essentially been storyboarding our research.

Storyboarding is a term often associated with film industry creatives, who use the process not only to make a concrete visualization of narrative ideas, but also to start calculating what their final production will entail in terms of collaborations and costs.

People have specifically recommended storyboarding for academic writers because they also need to flesh out complex ideas and keep track of many minor points over the course of a long project.

If you’re like Mirela and me, you need to physically manipulate as well as see your thoughts on a page of some kind.

But there are also many more technologically savvy options out there if you’re so inclined. Some people storyboard with programs like PowerPoint. Widely used platforms like Canva also have tools specifically created to help people make storyboards.

In any case, the point is to visualize your thoughts, relishing the productive discomfort that keeps you scribbling, pinning, or typing until your ideas start gaining clarity and coherence.

When I shared my findings about storyboarding with Mirela, she replied, “So, in conclusion we are in fact film directors in disguise.”

What a great image! I like how she thinks.

Thank you, Mirela, for inspiring this post! To everyone else, please be in touch if you have feedback or ideas for future posts to share.